INSIGHTS

Surveying Practicing Firearms Examiners

OVERVIEW

In recent years, there has been much discussion and debate regarding firearm examiner testimony, but little is known empirically about the actual practices of firearm examiners in conducting casework. Researchers funded by CSAFE conducted a survey of practicing firearms examiners to better understand the conditions of their casework, as well as their views of the field and its relations with other parts of the justice system.

Lead Researchers

Nicholas Scurich

Brandon L. Garrett

Robert M. Thompson

Journal

Forensic Science International: Synergy

Publication Date

2022

Publication Number

IN 127 IMPL

Goals

1

2

Find what examiners believe impacts the quality of their work

3

Learn the examiners’ opinions of statistical models, new technology, and misunderstandings from judges and jurors in regard to their profession

The Study

Scurich et al. posted a survey on the Association of Firearms and Toolmark Examiners (AFTE) member forum from July to November of 2020. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and uncompensated. A total of 79 AFTE members provided usable responses.

The survey asked about several topics, including:

- How much time is spent on a typical firearms case examining and comparing bullets or cartridge cases

- The percentage of identifications, exclusions, and inconclusive results in their casework

- The perceived industry-wide false positive error rate of firearms and toolmark work as a whole

- What factors affect the quality or quantity of their casework

- What judges and jurors misunderstand about firearm examination

- What role if any firearm examiners believe statistics should play in firearms analysis

Results

Frequency

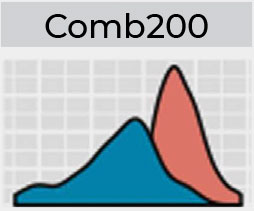

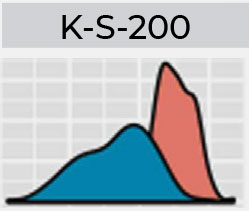

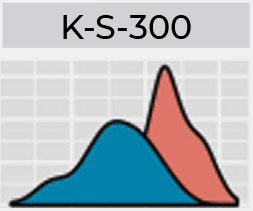

What percentage of your cases result in an identification conlusion?

Frequency

What percentage of your cases result in an exclusion/elimination conlusion?

The percentage of identification results vs. elimination results

From the 79 responses, Scurich et al. learned the following:

- Examiners took an average of 2-4 hours on bullet examinations and 1-2 hours on cartridge examinations.

- A median 65% of cases resulted in an identification conclusion.

- On average, participants reported that 12% of cases resulted in an exclusion or elimination, while 20% resulted in an inconclusive decision.

- Verifiers rarely if ever disagreed with the examiners’ conclusions.

- When asked of the industry-wide false positive error, the median response was 1%. Many participants were not able to name a specific study to support this observation.

- Factors that affected the quality of examiners’ work included the quality of the evidence itself, the quality of available equipment, and pressure for faster turnaround times.

- Opinions on the role that statistics might play in the future ranged widely, with some considering it a potentially helpful tool, and others calling it unnecessary or even detrimental to their work.

Focus on the future

Further work should explore the impacts of lab policies and evidence submission practices on examiners.

New training and educational opportunities—for both firearm examiners and the consumers of firearm examiner testimony—could provide benefits and promote clearer understanding of the strengths and limitations of firearm examination.