Is the field of science-based solely on logic and facts? A closer look reveals that science is not always as systematic and foolproof as we may think.

Scientists are humans, not robots. As such, the field of science has the potential to be compromised by human error, bias and other cognitive factors.

CSAFE researchers and psychologists Dr. Daniel Murrie and Dr. Sharon Kelley from the University of Virginia describe how human factors can influence the accuracy of scientific work as a whole, and the specific impact they can have on forensic science.

Defining Human Factors

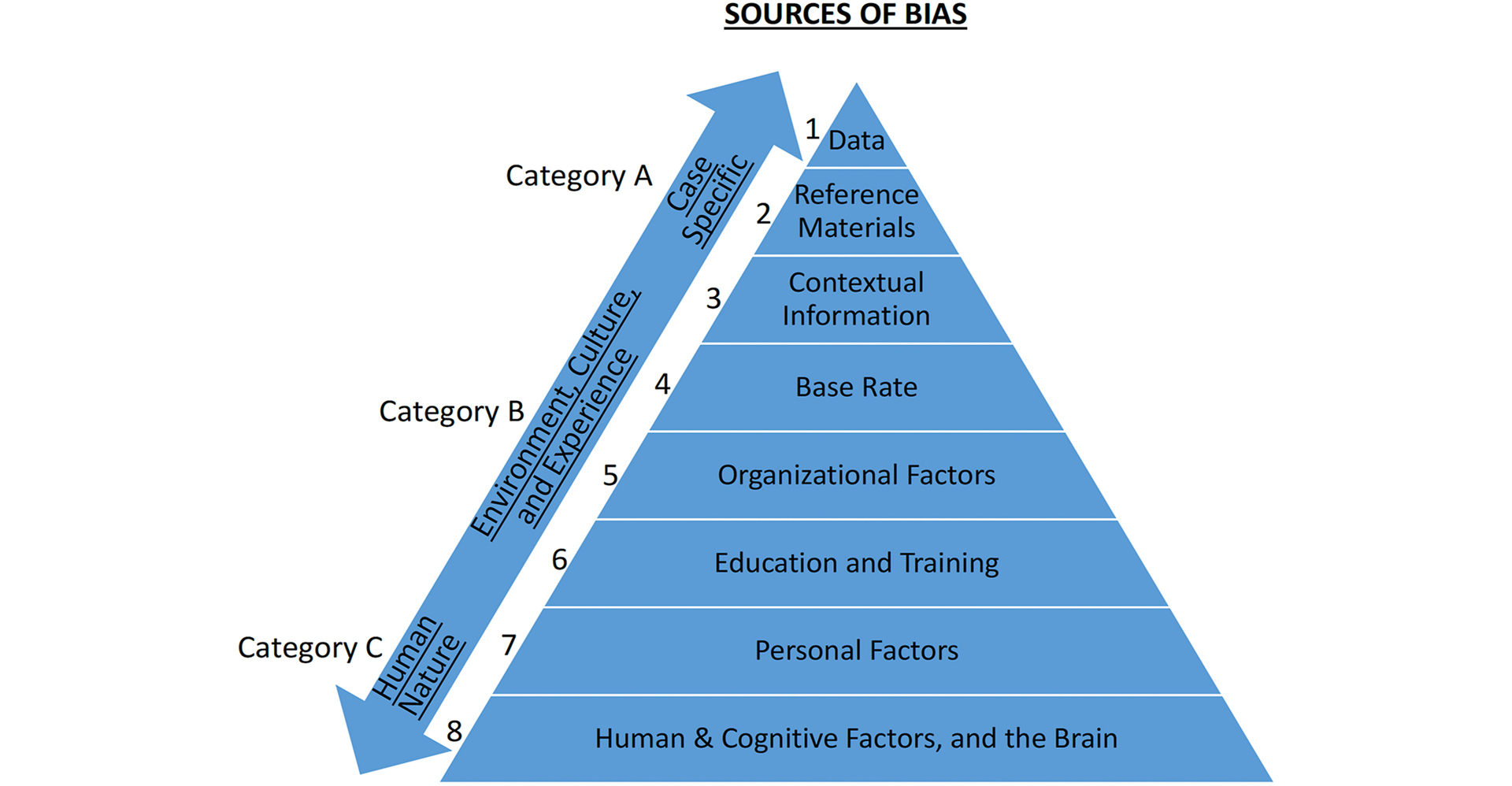

Dr. Murrie explains that human factors are relevant any time that the human mind or behavior is part of the scientific process. “Human factors, including cognitive bias, can influence how we collect and analyze data, or how we communicate the findings,” he said.

The human brain is powerful and typically steers us in the right direction.

“Our minds are very efficient and that usually serves us well,” Murrie said. “Our brains develop many shortcuts or heuristics that help us make reasonably good decisions fast.”

While this approach to decision making seems practical and beneficial, it has a downside.

“There are a few times when that cognitive infrastructure can lead us to take short cuts or jump to conclusions,” Murrie said. “This can leave us vulnerable to bias in ways that aren’t helpful to science, accuracy or objectivity.”

Human Factors in Forensic Evidence Analysis

The 2009 NAS report calling for reform in forensic science has led to more awareness of human factors and driven new research on cognitive bias in evidence analysis.

For instance, when a fingerprint or shoeprint examiner compares the print of a suspect to a print from the crime scene, there is potential for human factors to bias the examiner’s decision on a match.

Dr. Kelley explains how.

“General social and cognitive psychology research indicates that (A) humans often see what they expect to see and that (B) humans tend to seek out and interpret information in a way that supports their pre-existing beliefs,” she said.

For example, forensic science examiner may have had an opinion about the guilt or innocence of a suspect before even beginning the examination. Whether intentional or not, it could lead to biased results.

Dr. Kelley emphasizes that forensic scientists must be aware of potential bias before expressing opinions or decisions on the outcome of evidence analysis.

Why Is Awareness of Bias, not Enough?

“The good news is that awareness of biases in forensic science is probably at an all-time high. The bad news is that people don’t quite know what to do with this new awareness,” Murrie said.

One concern from recent research is the “bias blind spot,” as cognitive psychologists call it.

“People generally recognize that bias is a problem, but they only see it in others—not themselves,” Murrie said.

Kelley explains that for those who do recognize their own biases, it’s hard to change on your own.

“Introspecting and knowing about the bias and then just trying hard not to be biased is not enough,” Kelley said. “We know from research that these biases often aren’t conscious and you can’t just scan yourself and check for them. Biases still creep into our decision making.”

Instead of squinting your eyes and focusing hard not to be biased, Kelley says procedural and systematic changes are needed.

Strategies to Lessen the Impact of Human Factors in Crime Labs

According to Kelley, crime labs are a very heterogeneous group. They differ in their understanding of cognitive bias and strategies to combat the issue.

So how can researchers like Murrie and Kelley help crime labs reduce the impact of human factors in their investigations?

Two strategies CSAFE is working on to reduce bias are blind verification procedures and context management.

Blind verification procedures serve as checks and balances when analyzing evidence. In this method, a second examiner reviews a case with no information about what the first examiner concluded. Crime laboratories then have two independent decisions to compare. When the two examiners agree, there is more confidence that the analysis is accurate.

Context management involves limiting unnecessary contextual information about the suspect or the crime scene that is irrelevant to the evidence analysis task. For example, when comparing a set of fingerprints, the examiner doesn’t need to know the race or criminal record of the suspect, or even the results of DNA analyses, to do their job. Reducing potentially biasing information increases objectivity in evidence analysis.

Read more about how CSAFE research is addressing context management in crime laboratories.