INSIGHTS

Treatment of Inconclusives in the AFTE Range of Conclusions

OVERVIEW

Several studies have estimated the error rates of firearm examiners in recent years, most of which showed very small error rates overall. However, the actual calculation of these error rates, particularly how each study treats inconclusive results, differed significantly between studies. Researchers funded by CSAFE revisited these studies to see how inconclusive results were treated and how these differences impacted their overall error rate calculations.

Lead Researchers

Heike Hofmann

Susan Vanderplas

Alicia Carriquiry

Journal

Law, Probability and Risk

Publication Date

September 2020

Publication Number

IN 113 FT

THE GOALS

1

Survey various studies that assess the error rates of firearms examinations.

2

Determine the differences in how inconclusives are treated in each study.

3

Identify areas where these studies can be improved.

The Study

Hofmann et al. surveyed the most cited black box studies involving firearm and toolmark analysis. These studies varied in structure, having closed-set or open-set data. They were also conducted in different regions, either in the United States and Canada or in the European Union. The most relevant difference, however, was how each study treated inconclusive results.

All studies used one of three methods to treat inconclusives:

- Option 1: Exclude the inconclusive from the error rate.

- Option 2: Include the inconclusive as a correct result.

- Option 3: Include the inconclusive as an incorrect result.

Key Terms:

Black Box Study: a study that evaluates only the correctness of a participant’s decisions.

Closed-set Study: one in which all known and questioned samples come from the same source.

Open-set Study: one in which the questioned samples may come from outside sources.

Results

Option 1 was deemed inappropriate for accurate error rates. Option 2 was useful for error rates of the individual examiners, while Option 3 reflected the error rates of the process itself.

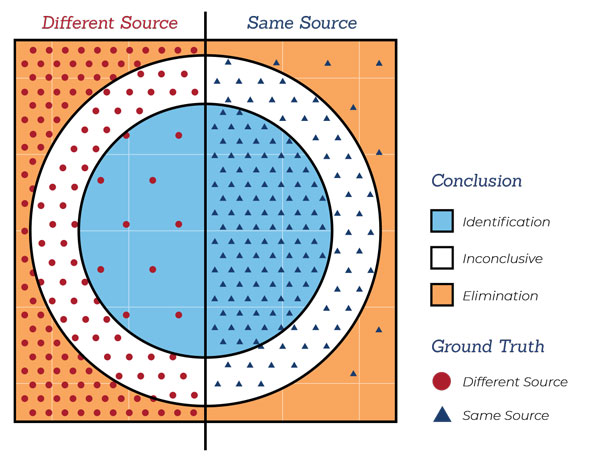

Examiners tended to lean towards identification over inconclusive or elimination. In addition, they were far more likely to reach an inconclusive with different-source evidence, which should have been an elimination in nearly all cases.

Process errors occurred at higher rates than examiner errors.

Design issues created a bias toward the prosecution, such as closed-set studies where all samples came from the same source, prescreened kit components which inflated the rate of identifications, or multiple known sources which could not quantify a proper error rate for eliminations.

Fig. 1. Sketch of the relationship between ground truth of evidence (dots) and examiners’ decisions (shaded areas). In a perfect scenario dots only appear on the shaded area of the same colour. Any dots on differently coloured backgrounds indicate an error in the examination process.

FOCUS ON THE FUTURE

Hofmann et al. propose a fourth option:

- Include the inconclusive as an elimination.

- Calculate the error rates for the examiner and the process separately.

While most studies included a bias toward the prosecution, this was not the case for studies conducted in the European Union. Further study is recommended to verify this difference and determine its cause.