A recent study from the Center for Statistics and Applications in Forensic Evidence (CSAFE) examined the effects of blind proficiency testing and cross-examinations in juror appraisals of forensic examiner’s testimony. The study was published in Forensic Science International.

Forensic testimony plays a crucial role in many criminal cases, with requests to crime labs steadily increasing. As part of efforts to improve the reliability of forensic evidence, scientific and policy groups are increasingly recommending routine blind proficiency tests of forensic practitioners.

William Crozier, research director of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke University and co-author of the study, said that as blind proficiency testing becomes more widespread, the results of such tests are likely to be reported and the subject of forensic examiners’ testimony in court. However, what is not known is how doing so affects how jurors assess testimony by forensic practitioners in court, he said.

Crozier set out to examine how knowledge of a forensic examiner’s performance on a blind proficiency test affects the jurors’ confidence in their testimonies. In addition to Crozier, the research team included Jeff Kukucka, associate professor of psychology at Towson University; and Brandon Garrett, CSAFE co-director and the L. Neil Williams, Jr. Professor of Law and director of the Wilson Center for Science and Justice.

They conducted two studies where two separate groups read a mock trial transcript in which a forensic examiner provided the central evidence. In both studies, participants were asked to render a verdict, estimate the likelihood that the defendant committed the crime and provide opinions on the examiner and the evidence. However, in Study 2, participants received the same testimony, but for some conditions, the examiner was cross-examined by the defense attorney.

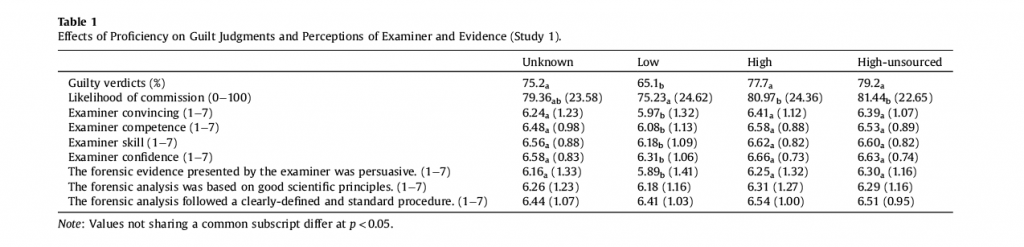

Participants read examiner testimony based on four blind proficiency test score scenarios: the examiner reported that he had made zero errors (high proficiency), made six mistakes in the past year (low proficiency), claimed high proficiency without proof (high, unproven proficiency), or did not discuss his proficiency at all (control).

Crozier and his colleagues found that stating proficiency scores did influence the participants’ verdicts. In Study 1, the low-proficiency forensic examiner elicited a lower conviction rate and less favorable impressions than the control. However, the high-proficiency examiner did not correspondingly elicit a higher conviction rate or more favorable impressions than the control.

In Study 2, the researchers found that cross-examination significantly reduced guilty votes and examiner ratings for low-proficiency examiners. The high-proficiency examiner received more convictions and withstood cross-examination better than the other examiners.

Overall, despite having lower conviction rates, the low-proficiency examiners were still viewed very favorably and still achieved convictions most of the time in both studies.

“These two studies shed light on how jurors react to and utilize information about an individual forensic examiner’s performance on blind proficiency tests,” said Crozier. “The results suggest that blind proficiency testing information can valuably inform jury decision-making.”

The researchers found that the examiners were not severely undermined by jurors even when their proficiency scores were low or subjected to intense cross-examinations. Crozier said forensic examiners should not fear that blind proficiency testing would create unwarranted challenges in presenting expert testimony in court.

“These studies support the use of blind proficiency testing more routinely, and test results can usefully inform trials and should be incorporated into the evidence that jurors consider at criminal trials,” he said.

View and download the journal article at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/csafe_pubs/76/.

View insights from this study: https://forensicstats.org/blog/2020/10/10/insights-juror-appraisals-of-forensic-science-evidence/.

This study was a topic of the recent CSAFE webinar, Mock Juror Perceptions of Forensics. The recording is available at https://forensicstats.org/blog/portfolio/mock-juror-perceptions-of-forensics/.