INSIGHTS

Using Mixture Models to Examine Group Differences Among Jurors:

An Illustration Involving the Perceived Strength of Forensic Science Evidence

OVERVIEW

It is critically important for jurors to be able to understand forensic evidence,

and just as important to understand how jurors perceive scientific reports.

Researchers have devised a novel approach, using statistical mixture

models, to identify subpopulations that appear to respond differently to

presentations of forensic evidence.

Lead Researchers

Naomi Kaplan-Damary

William C. Thompson

Rebecca Hofstein Grady

Hal S. Stern

Journal

Law, Probability, and Risk

Publication Date

30 January 2021

Publication Number

IN 116 IMPL

Goals

1

Use statistical models to determine if subpopulations exist among samples of mock jurors.

2

Determine if these subpopulations have clear differences in how they perceive forensic evidence.

THE THREE STUDIES

- In three different studies, diverse groups of jury-eligible adults evaluated pairs of statements regarding forensic evidence and judged which statements they felt were stronger.

- Each study used different forensic evidence types and different presentations of data, e.g., numbers-based “quantitative” statements and more categorical, “qualitative” statements.

- The studies measured five participant characteristics: gender, age, numeracy (ability to work with numbers), education level, and forensic knowledge.

- Researchers analyzed the participants’ responses, first using an exploratory analysis which hypothesizes differences in subpopulations defined by characteristics such as age. Then they utilized the novel mixture model approach to examine the data.

Definition:

Mixture model approach:

a probabilistic model that detects

subpopulations within a study population empirically, i.e., without a priori hypotheses about their characteristics.

Results

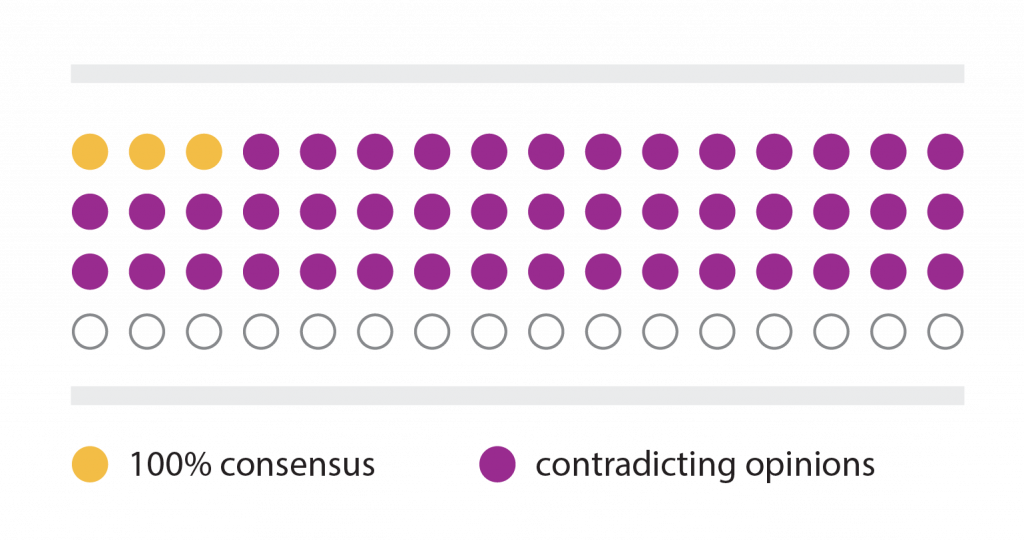

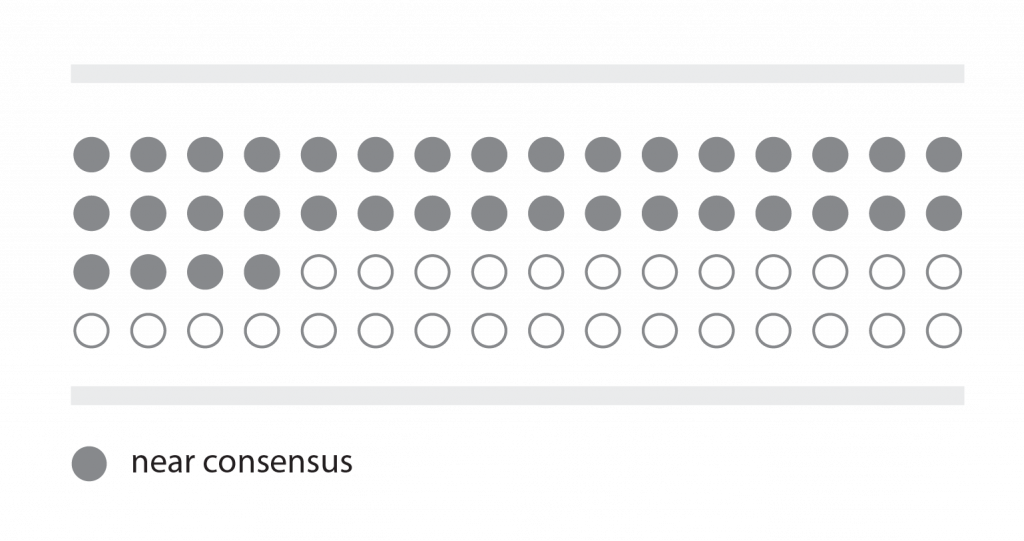

- Data from the three studies suggest that subpopulations exist and perceive statements differently.

- The mixture model approach found subpopulation structures not detected by the hypothesis-driven approach.

- One of the three studies found participants with higher numeracy tended to respond more strongly to statistical statements, while those with lower numeracy preferred more categorical statements.

higher numeracy

lower numeracy

Focus on the future

The existence of group differences in how evidence is perceived suggests that forensic experts need to present their findings in multiple ways. This would better address the full range of potential jurors.

These studies were limited due to relatively small number of participants. A larger study population may allow us to learn more about the nature of population heterogeneity.

In future studies, Kaplan-Damary et al. recommend a greater number of participants and the consideration of a greater number of personal characteristics.