On June 23, the Center for Statistics and Applications in Forensic Evidence (CSAFE) hosted the webinar, Blind Testing in Firearms Examination: Preliminary Results, Benefits, Limitations, and Future Directions. It was presented by Maddisen Neuman, a Quality / Research Associate at the Houston Forensic Science Center (HSFC).

In the webinar, Neuman shares the methodology for HSFC’s blind proficiency testing program, as well as results from a recent study of 51 blind cases submitted to examiners between 2015 and 2021.

If you did not attend the webinar live, the recording is available at https://forensicstats.org/blog/portfolio/blind-testing-in-firearms-examination/

Why is blind testing important?

If an examiner knows they are being tested, results from a study can be skewed, so several governing bodies in the forensic science community recommend conducting blind proficiency tests to achieve more precise results. Researchers can do this by inserting test samples into the flow of casework so examiners do not know that they are being tested.

HSFC implemented its blind quality control program in 2015 and creates mock case evidence in house, with the goal of submitting test material at a rate of five percent of each section’s output from the year before.

Why is the advantage of having a blind testing program?

The biggest advantage is having a ground truth against which to compare examination results, which is not known in normal casework. Additionally, because examiners aren’t aware which cases are test cases, they perform the work as they would for a normal case. This allows researchers to observe the entire examination process, from evidence submission to the reporting of results.

How are firearms blind cases designed and submitted?

Blind cases mimic routine evidence and cases in order to appear authentic. The firearm used to create the fired evidence may or may not be submitted as an additional piece of evidence. Though HFSC has a large reference collection, blind tests are not created from this library as the examiners are likely to recognize the evidence. Some fired evidence is created using personal firearms from employees of HFSC.

HFSC researchers have also developed a partnership with the Houston Police Department (HPD), and regularly use firearms the property room division has slated for destruction to create mock evidence for blind testing. These firearms are often representative of the types of firearms seen frequently in casework.

Fired evidence is then marked or documented in a way that relates it back to its corresponding firearm. Cartridge casings and bullet jackets are submitted with ground truths of either identification or elimination. Fragments and bullet cores are expected to be unsuitable or insufficient regardless of which firearm was used to create the evidence.

When a case is ready, it is packaged just like a regular firearms case would be, in an envelope or gun box. Technicians take the evidence to the HPD property room and prepare it with an HPD evidence bar code. The evidence stays there until HFSC makes a request for analysis, enlisting the help of HPD officers who use their names on the request, thus keeping the test blind. When the evidence arrives at HFSC for processing, it is assigned as usual by managers and supervisors who themselves do not know which evidence is real casework and which is test material.

What are the range of results expected from a blind proficiency firearms test?

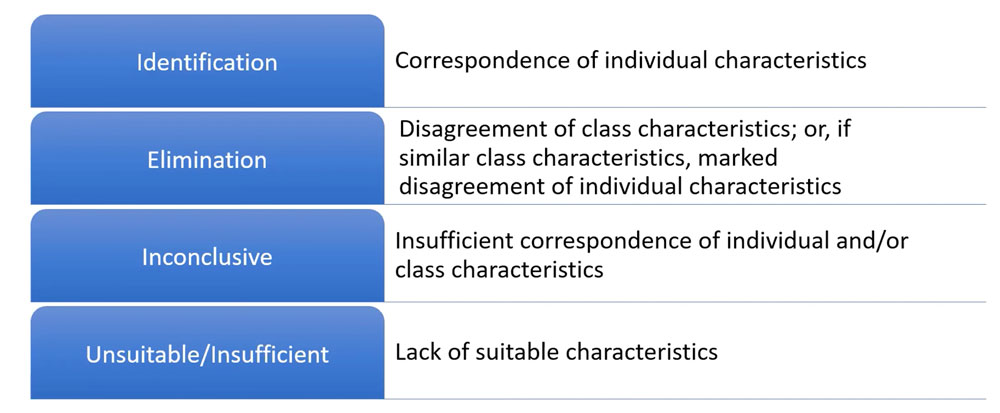

The range of results expected in HSFC’s blind proficiency test program follow the standard operating procedures widely used within the community. A condensed version of the results expected include:

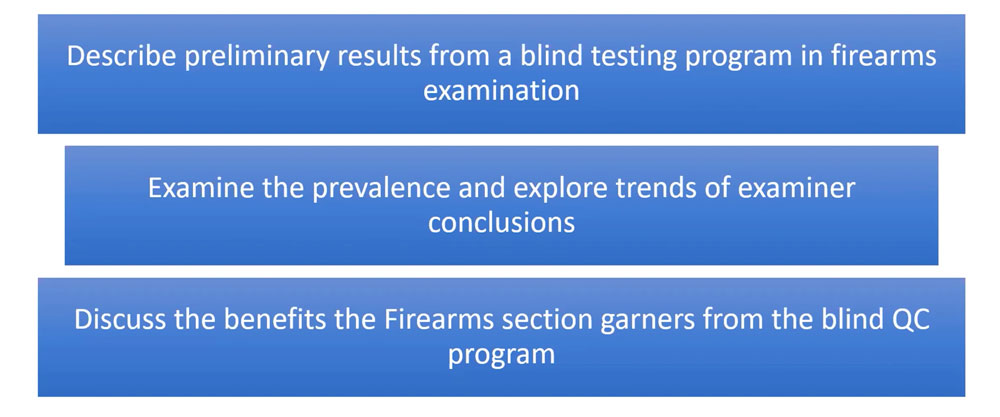

What are the objectives of HFSC’s blind proficiency tests?

What were the parameters and results of HSFC’s most recent study?

- Test results were received from December 2015 to June 2021.

- 51 cases were reported.

- 460 items were examined.

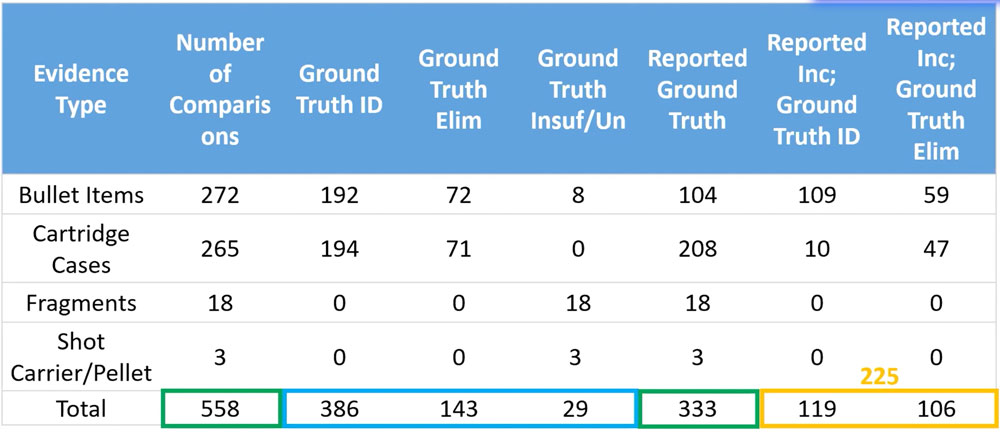

- 570 sufficiency and comparison conclusions were submitted, including:

- 386 identification

- 143 elimination

- 29 insufficient/unsuitable

- 12 items eliminated from study because ground truth could not be re-established after examination.

- 11 examiners

Preliminary results

What are some trends in the results?

- There was a 40 percent inconclusive rate throughout the course of the study.

- There was a higher rate of inconclusive results when the ground truth was elimination (74 percent of elimination results reported inconclusive) as opposed a ground truth of identification (31 percent of identification results reported as inconclusive).

- Bullets had a higher inconclusive rate than cartridge cases (62 versus 22 percent).

- Inconclusive decisions were made in 86 percent of comparisons in which the evidence was created using two firearms of the same class.

- Inconclusive decisions did not appear to be related to examiner pairings, experience, or the examiner’s training program.

What are the benefits of blind testing?

- Blind tests provide a more controlled environment in which to examine inconclusive results.

- Blind testing can gauge proficiencies in areas that normal proficiency tests don’t always cover (e.g., including evidence spanning cartridge cases, bullets, fragments, and firearms rather than just bullets or cartridge cases).

- More challenging case scenarios can be created to test the examiners’ thresholds for conclusions.

- Citing blind proficiency test results gives examiners the opportunity to bolster their credibility in court.

What are the next steps for HSFC’s blind testing program?

In the next phase of HSFC’s blind testing program, researchers would like to:

- Compare the program’s inconclusive rates to those found in real casework.

- Examine the consultation rate in the blind verification program.

- Use blind cases for training new examiners and assessing new technology.

- Collaborate with other labs and researchers to further this research.