INSIGHT

Psychometric Analysis of Forensic Examiner Behavior

OVERVIEW

Understanding how fingerprint examiners’ proficiency and behavior influence their decisions when interpreting evidence requires the use of many analytical models. Researchers sought to better identify and study uncertainty in examiners’ decision making. This is because final source identifications still rely on complex and subjective interpretation of the evidence by examiners. By applying novel methods like Item Response Theory (IRT) to existing tools like error rate studies, the team proposes a new approach to account for differences among examiners and in task difficulty levels.

Lead Researchers

Amanda Luby

Anjali Mazumder

Brian Junker

Publication Date

June 13, 2020

Journal

Behaviormetrika

Publication Number

IN 107 LP

THE GOALS

1

Survey recent advances in psychometric analysis of forensic decision-making.

2

Use behavioral models from the field of Item Response Theory to better understand the operating characteristics of the identification tasks that examiners perform.

APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

The Data

A 2011 FBI Black Box study assigned 169 fingerprint examiners a selection of items to analyze, which included a latent print evaluation, a source destination, a reason and a rating of the difficulty of the task for each pair of prints.

Key Definitions

Psychometrics

Using factors such as aptitudes and personality traits to study the difference between individuals.

Item Response Trees (IRTrees)

Visual representation of each decision an examiner makes in the process of performing an identification task. Based on IRT, which attempts to explain the connections between the properties of a test item –– a piece of fingerprint evidence –– and an individual’s –– a fingerprint examiner’s –– performance in response to that item.

Cultural Consensus Theory (CCT)

A method that facilitates the discovery and description of consensus among a group of people with shared beliefs. For this study, CCT helps identify the common knowledge and beliefs among fingerprint examiners –– things that examiners may take for granted but that laypeople would not necessarily know.

APPLYING IRTREES AND CCT TO FINGERPRINT ANALYSIS

1

Researchers segmented the data with the Rasch Model to separate a latent print’s difficulty level from an examiners’ proficiency. This allowed comparison to the existing method of studying error rates.

2

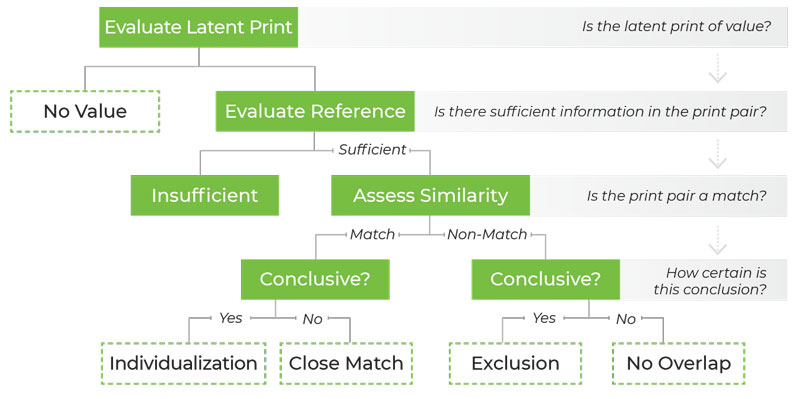

Then they constructed IRTrees to model a fingerprint examiner’s decision-making process when deciding whether a print is a positive match, negative match, inconclusive, or has no latent value. (See Figure 1)

3

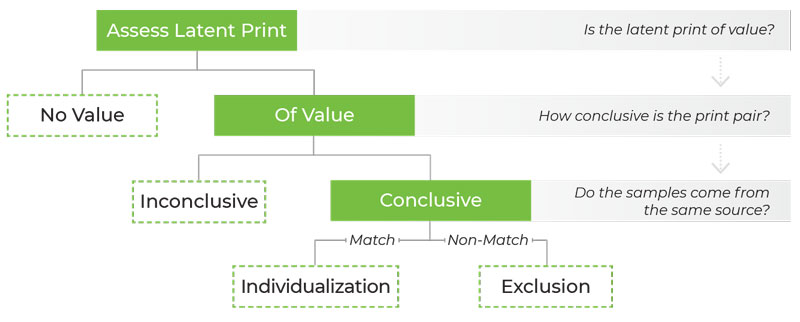

Finally, the team used IRTrees and Cultural Consensus Theory to create “answer keys” –– a set of reasons and shared knowledge –– that provide insight into how a fingerprint examiner arrives at an “inconclusive” or “no value” decision. (See Figure 2)

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR PRACTITIONERS

1

Using IRT models provides substantial improvement over current examiner error rate studies. These include the ability to justifiably compare examiner proficiencies

even if they did not do the same identification tasks and that the influence of task difficulty can be seen in examiner proficiency estimates.

2

IRTrees give researchers the ability to accurately model the complex decision-making in fingerprint identification tasks –– it is much more than simply stating a print is a “match” or a “non-match.” This reveals the skill involved in fingerprint examination work.

3

Examiners tend to overrate the difficulty of middling-difficulty tasks, while underrating the difficulty of extremely easy or extremely difficult tasks.

FOCUS ON THE FUTURE

This analysis was somewhat limited by available data; for confidentiality and privacy considerations, the FBI Black Box Study does not provide the reference prints used nor the personal details of the examiners themselves. Future collaboration with experts, both in fingerprint analysis and human decision making, can provide more detailed data and thus improve the models.